Pigou, Keynes and Shiller all recognised the importance of narratives and sentiment for the economy. But we don’t know too much about how narratives spread. One of the most powerful ways to find out would be to run a randomised controlled experiment that surfaces a particular narrative and then tries to measure how much that narrative catches on.

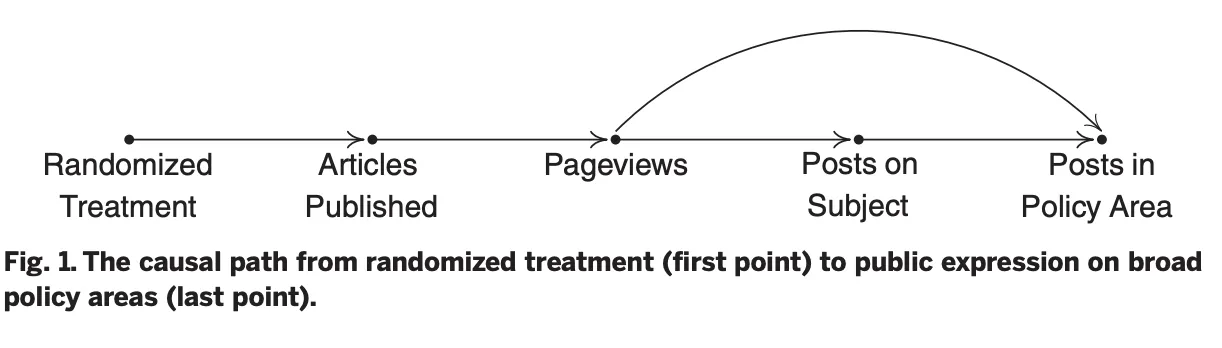

King, Schneer, and White (2017), writing in the journal Science, have come admirably close to an experiment which does just this. Their interest was more general than just economic narratives. They managed to cajole 48 media outlets into taking part in a randomised trial in which articles were published on the same topic on the same date. As they say, “Our unit of treatment was the entire nation during an experiment-week”. Following publication of the articles, the researchers monitored Twitter to see if the topics they had pushed did get picked up. Astonishingly, their intervention increased the volume of tweets on that topic by ~60%. Not only that, but the number of unique authors tweeting about the topic increased too.

Perhaps the most interesting result is that the experiment seemed to help change the narrative,

“Our news media intervention also changed the composition of opinion expressed in the national conversation by 2.3 percentage points in the ideological direction conveyed by our published articles; individuals may or not have been persuaded to change their views, but the overall testimony given publicly changed noticeably”

This is fascinating, and perhaps a bit scary, in light of the recent interest in fake news and narrative-based political interference. It also seems to run counter to the idea of confirmation bias.

Good science is rarely easy, and this was no exception;

“The difficulty is compounded by the fact that we asked these professionals to take actions few journalists have ever before agreed to, to allow researchers to participate in ways that rarely happen, and to share proprietary information with us that they do not even share with each other. We also needed to secure numerous individual agreements and arrange large-scale coordination among competing entities over nearly 5 years. As such, much of our effort involved building relationships, trust, and common understanding. We designed our experimental protocol to ensure that both our scientific goals and the journalists’ professional goals were maximized”

Expectations drive modern structural macroeconomic models, and narratives drive expectations, so this work has implications for understanding the ‘animal spirits’ of the economy. Narratives in newspapers, especially those with high circulation, could be important drivers of expectations amongst consumers.

I personally think that there’s more work to be done in understanding the narratives expressed in popular media. I’m interested in research which goes in this direction but, as these authors explain, there are many practical barriers to finding good empirical answers to even the most basic questions.